[Editor’s note: the following is adapted from the essay, Lessons from Cities and the Wealth of Nations: a manual for urban policymakers with permission from the author.]

Focus on cultivating import-replacement

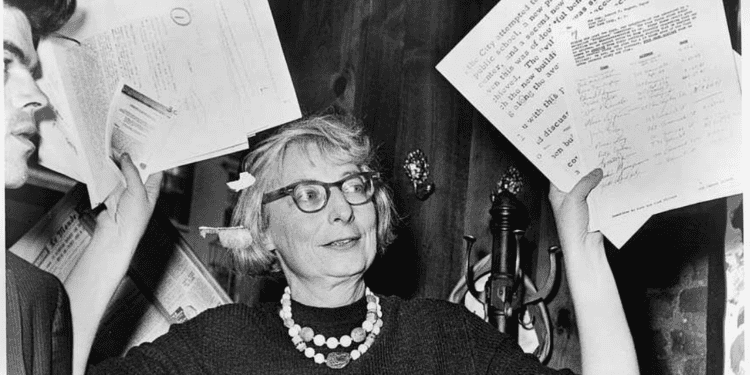

The economies of cities do not grow out of nothing. They grow by adding productive new forms of work to old ones, by innovating, and by being cultivators of new ideas and techniques. This process of cataclysmic growth – that Jane Jacobs describes as ‘import-replacement – occurs when a city takes its existing imports and builds upon them, either improving its production through lowering costs, increasing quality, or innovating. The market for these additional goods can either be found within the city itself or serves to expand the city’s exports. These exports, in turn, bring in additional resources to either acquire additional imports or be reinvested into fuelling the processes that fuel import-replacement. Not for nothing does Jacobs describe import-replacement as a ‘cataclysmic’ process – these changes often happen over a very short period and can bring about a rapid influx of people, ideas and capital. We see this in New York City, which grew from half a million residents in 1850 to over 3.4 million at the dawn of the twentieth century. Detroit went from having 250,000 residents in 1900 to a peak of 1.8 million by 1950. Delhi went from a population of 1.4 million in 1950 to almost 33 million in its larger metropolitan area today. That import-replacement is such a simple idea also makes it one of the most crucial to understand for policymakers. At the end of the day, a city can provide everything it wants in terms of amenities, sprawling parks, leisure centres and cultural venues, but without that fundamental process of import-replacement taking place, an urban agglomeration will not grow and will be confined to decline. To quote Jacobs: ‘artificial symptoms of prosperity or a “good image” do not revitalize a city, but only explicit economic growth processes for which there are no substitutes.’ (The Economy of Cities, Pg 200).

So much for that idea; it is clear that import-replacement must be at the heart of any policy for urban development. How can policymakers leverage this idea when it seemingly depends so much on individual decisions made by companies and entrepreneurs? The first thing to address is what are the barriers that prevent economic import-replacement? Are land-use patterns overly strict and restrictive to new and innovative types of industry? Central to the idea of import-replacement is the idea that new forms of businesses, processes and industries will arise that cannot be foreseen in advance. It is therefore crucial that land-use regulation permits new forms of industries to emerge.

The process that Jacobs describes transcends individual policymakers, instead relying on decisions by financial institutions, entrepreneurs, and thrifty individuals. This should not lead to hopelessness. I would argue (and Jacobs, through her expansive uses of historical examples) that enterprise and trade come very naturally to human beings if the conditions are right. Whilst this does not guarantee that any city can become an economic powerhouse, since important factors including geography, human capital, and chance also play an important role, almost every region contains a dominant urban agglomeration. By minimising barriers to trade and commerce in these areas, ensuring regulation, taxes and land-use is conducive to growth rather than acting as a resistor, cities can begin to tap into the power of import-replacement and grow their economies and those of the regions surrounding them.

Finally, where I diverge from the libertarian-purist perspective is that I argue urban policymakers can play an active role in cultivating growth. For example, by creating forums for entrepreneurs to come together and exchange ideas, encouraging universities to collaborate with businesses so that jobs are created within the city (see HEC Paris’ incubator), and making sure the basic needs of the city (sanitation, safety, etc) are met, cities can help to kick-start the process of import-replacement.

One policy that seldom works, however, is offering large subsidies to companies to locate in a city – often in the form of tax breaks or land grants. There is significant literature outlining how this greatly distorts the allocation of resources on a national (and international) scale. Yet the idea is nonetheless tempting to policymakers if they think it’ll bring regional benefits. The research on this does not suggest this is the case – as highlighted in a recent essay published by the Center for American Progress. Jacobs provides a clear reason for why this is the case in both The Economy of Cities and Cities and the Wealth of Nations. Put simply, big businesses which are ‘transplanted’ into smaller cities do not bring about import-replacement because they are already tightly vertically integrated. Smaller businesses, however, are more likely to tap into an existing or nascent eco-system of other businesses – in a city or elsewhere – to produce its goods. This greatly increases the likelihood of innovation and new techniques being adopted as competitors strive to improve quality and lower prices. Money spent on providing large subsidies can therefore be put to much more effective use if it is instead returned to businesses as a tax cut or channelled into the other factors that encourage import-replacement.

Look at what your city does well

It is not the case that cities can purchase development by simply luring in companies, through tax breaks or other means, to set up transplants in their regions. ‘Development cannot be given, it has to be done. It is a process, not a collection of capital goods,’ notes Jane Jacobs on page 119 of Cities and the Wealth of Nations. For urban policymakers, the lesson that can be drawn from this is that the focus should be placed on the existing things a city or metropolitan area does well. It would be nonsensical for a city like Fort Wayne, Indiana, to spend billions of dollars trying to become the next Silicon Valley. Agglomeration effects matter and remain a central part of how import-replacement happens. For more effective, for small and medium-sized, is to focus on what they already do well and aim to cultivate those industries. This is less difficult than it seems for again, individuals and businesses have a remarkable ability to innovate and lead the import-replacement process themselves if the conditions are right. For urban policymakers, the focus should therefore be on identifying bottlenecks in cooperation. Are land prices prohibitive to the creation of new industries and could zoning reform unlock additional growth? Is the city the kind of place that would attract potential talent, or is crime, housing availability and educational provision undermining its ability to do so? Again, whilst actively picking and choosing winners and losers seldom works, there is an active role that policymakers can play in helping to cultivate growth in existing sectors that are performing well. Cities could partner with chambers of commerce to ensure that businessmen are connected, and ideas spread faster. Collaboration with banks and financial institutions could provide seed money for new businesses to emerge. By first focusing on the basics, then looking at the particular areas of success and finding ways to encourage them further, a city can help kick-start the growth-replacement process.

Beware of over-specialisation

Import-replacement depends on specialisation. Both Jacobs and later, Edward Glaeser (in Triumph of the City) highlight the importance of urban agglomerations which increase the spread of ideas and allow firms to produce new goods and ideas without having to start from scratch. Chris Miller’s Chip Wars provides a vivid description of how this process played out in Silicon Valley, noting how specialisation allows each company to focus on adding value at one specific part of the supply chain, to the point where countless companies now focus solely on chip design, others, like GlobalFoundries focus on manufacturing, yet others on marketing, transportation, the production of equipment. It is far easier to start a company in an environment where not every aspect of the supply chain needs to be replicated and companies instead tap into an existing eco-system. The odds of innovation grow significantly, as a result of lower barriers of entry.

Except over-specialisation is at cross-purposes with the long-term success of a city, if it means that it cannot recover or surmount shocks in global supply and demand. Take the classic example of Detroit, which specialised very heavily in automobile production over the first half of the twentieth century, this growth almost entirely led by private enterprise. When automation and increased foreign competition led to a decline in the Motor City’s primary industry, workers had few alternatives. Many just left, leading to a precipitous population decline from 1.8 million to just over 640,000 today.

I will again stress that a lot of the economic dynamics occurring within a city are not things that policymakers can directly control. Subsidies might work in the short term, but as noted above, their success is very limited in the long run and the money might instead have been returned to residents in the form of a tax cut. Furthermore, no single policy prescription will work for all cities, since each faces a unique set of problems and challenges and mayors must look closely at the problems confronting their particular city.

There are nevertheless some takeaways from Jacobs’ works that might apply here and that mayors and other urban leaders could take to their cities. First is that space and layout matter. Jacobs presents a view of cities that very heavily emphasises the importance of walkability and access. I would push back a little and say that perfect walkability is not always necessary. Yet enterprises and households should be in relative proximity to each other to foster greater exchange of ideas and collaboration. A fifteen-minute drive on the highway might not make a difference. A fifty-minute drive in chock-a-block traffic would. The other ingredients to fostering urban diversity (still allowing for specialisation but in various sectors) include mixed uses of land, sufficient density to provide businesses with customers, older buildings to allow for experimentation (new or experimental businesses often can’t afford new units where costs are very high), and smaller blocks to allow for more street frontage.

Jacobs’ analysis of the factors cultivating urban economic diversity is sound, but it requires further expansion if it is to apply to traditional industry and the new creative industries. In addition to these factors, cities and states should also ensure their processes allow for flexibility and collaboration with regard to permitting and other legislation; they should ensure their processes are clear and transparent, and they should keep costs at a minimum.

Simply wishing for prosperity won’t make it so. The reality is that urban success depends on governance, ideas, and some degree of luck. But another remarkable fact emerges from the literature of Jacobs’ and others I have buried myself in over the last few weeks: human beings have an incredible ability to collaborate and innovate if left to do so. It’s a hopeful takeaway, for it means that success doesn’t depend on policymakers’ abilities to play economic planners and run a city. Focus on the basics, eliminate barriers to growth, advocate for your city, and you may well turn the odds slightly in its favour.