It was the type of interaction that Twitter was made for. Former head of Toronto city planning Jennifer Keesmaat sends out a tweet extolling the virtues of a corner, neighborhood cafe. It’s lack of parking and proximity to housing keeps it walkable, which in turn fosters healthier communities.

In the replies, architecture critic Alex Bozikovic can’t agree more, suggesting that developments like this cafe should be allowed without having to “fight city planning.” Keesmaat quickly changes her tune, arguing that the cafe might have been a noise and sanitation nuisance, absent extensive planning review. A skeptical Bozikovic calls her bluff, pointing out that planning review for this particular cafe had nothing to do with nuisances, but succeeded in delaying its opening for years.

Vancouver housing activist Brendan Dawe captured the peculiar exchange with a succinct caption: “Urban Planning: a story in 4 acts.”

What did Bozikovic have in mind when he suggested that the cafe should be allowed without pushback from planners? Why did Keesmaat make a 180 on her view of the cafe? And what does this say about city planning?

To understand all this, you need to understand a concept that’s central to how we regulate land: as-of-right zoning.

Before the rise of zoning in the 1920s, land-use regulation could be a bit of a mess. Certain neighborhoods had height and density limits, while others didn’t. Use segregation often occurred on an ad hoc, use-by-use basis. These rules were often spread across multiple ordinances and maps, with no single document explaining what you could and couldn’t do. All of this meant that it was hard for developers to figure out what they could build and hard for residents to know what might spring up near them in the future.

Urban Planning: a story in 4 Acts: pic.twitter.com/k5RogKDmP4

— Brendan Dawe (@BrendanDawe) July 7, 2019

To deal with this problem, city planning boosters in the early twentieth century came up with a new way to regulate urban land: as-of-right zoning. Every part of the city would be broken out into districts, subject to different use and density rules. That’s the “zoning” piece that most readers will be familiar with. As long as developers stuck by those rules, they could build without any extra regulatory hassle. That’s the “as-of-right” piece that’s less well known.

We can all probably agree that the content of these rules often weren’t great. There’s wide consensus among planners today that minimum parking requirements and strict use segregation were a mistake, for example. That’s what Keesmaat was tapping into in her original praise for the corner cafe.

But in terms of the form, there’s a lot to like with as-of-right zoning. For starters, it gives everyone certainty about what can be built and where. For developers, that means no expensive delays, unexpected stipulations, or raucous public hearings, all of which make development more expensive and raise the cost of housing. For residents, that means no unexpected slaughterhouses or strip clubs next door.

A problem with contemporary city planning, as Bozikovic picked up on, is that we’re increasingly living in the worst of both worlds: On the one hand, anti-urban land-use ordinances are still on the books in most North American cities. But instead of scrapping these rules, cities are increasingly returning to an ad hoc, project-by-project system of land-use regulation, letting projects bypass the land-use ordinance in exchange for months — if not years — of added scrutiny. This is called “discretionary” permitting, as it puts permits at the discretion of local appointed planning commissions.

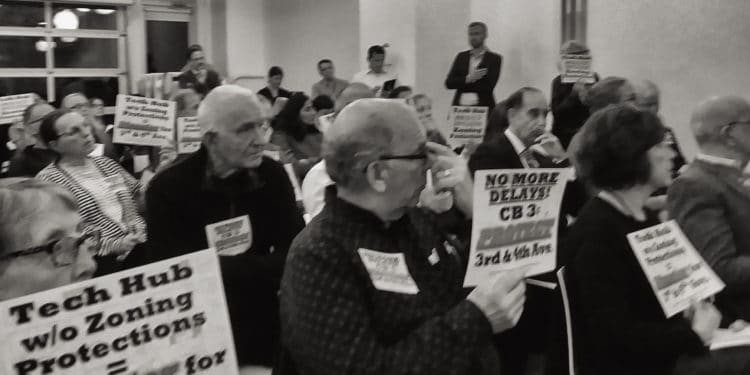

Discretionary review simply isn’t necessary or justified in most cases, and can often be weaponized by NIMBYs.

The steelman case for a return to discretionary permitting goes something like this: Each project is different. Local contexts vary too much and local residents may have strong feelings about how a project impacts them. The only way to keep everyone happy is to aggressively vet the potential impacts of every project, subjecting each proposal to public scrutiny and requiring specialized mitigation as may be necessary. This is what Keesmaat presumably had in mind when she cautioned against allowing the cafe as-of-right.

But there are a few problems with this position. For starters, added review simply isn’t necessary or justified in most cases, and can often be weaponized by NIMBYs. Discretionary approvals tend to treat every project like a potential major risk—bending over backwards to accommodate those who complain the loudest—when in reality, the impacts of most infill development are minimal and predictable. We can easily deal with them with rules that are clear and upfront, and save the intense scrutiny for unusual projects which pose real risks. A neighborhood cafe isn’t a landfill; why treat them the same?

All of this wouldn’t be an issue if the added process is harmless, but it isn’t. An overdependence on discretionary permitting can be inherently exclusionary to small developers—who may not have the in-house legal counsel needed to navigate this process—and small projects—which usually can’t sustain the added costs. This needlessly disadvantages the local builder who has the most skin in the game as far as building a great community while privileging the large national builders. It also disadvantages small projects, depriving communities of desirable infill developments.

If there’s room for agreement between Keesmaat and Bozikovic, it’s that the current anti-urban land-use ordinances on the books in most cities don’t make sense. But what’s the alternative? The emerging norm is for cities to regress to the kind of ad hoc regulation that preceded zoning, letting new projects bypass out-of-date rules after a long and chaotic review process, with public process reduced to project-specific shouting matches.

A more sustainable approach might simply be to overhaul the rules while maintaining as-of-right permitting. If run-of-the-mill projects are regularly bumping up against out-of-date rules, cities should bring stakeholders together and identify shared goals and concerns, draft clear and transparent rules that reflect these findings, and approve compliant projects without much fuss. You might even call it city planning.