But the duplex and triplex provisions of the plan haven’t led to much new housing. In fact, researchers and journalists have found that these rules have hardly affected Minneapolis housing development. Since 2013, developers have built only a few dozen 2-3 unit buildings under 2040 Plan rules.

But this does not mean that Minneapolis’s zoning reforms failed. While developers have built relatively few duplexes and triplexes since the 2040 Plan’s passage, they have built quite a lot of other multi-family housing in lower-density neighborhoods — it just happens to be the case that most of these projects are larger than three units. Rather than proving their inefficacy, Minneapolis’s success reaffirms the promise of well-executed “missing middle” zoning reforms.

Minneapolis’s New Homes

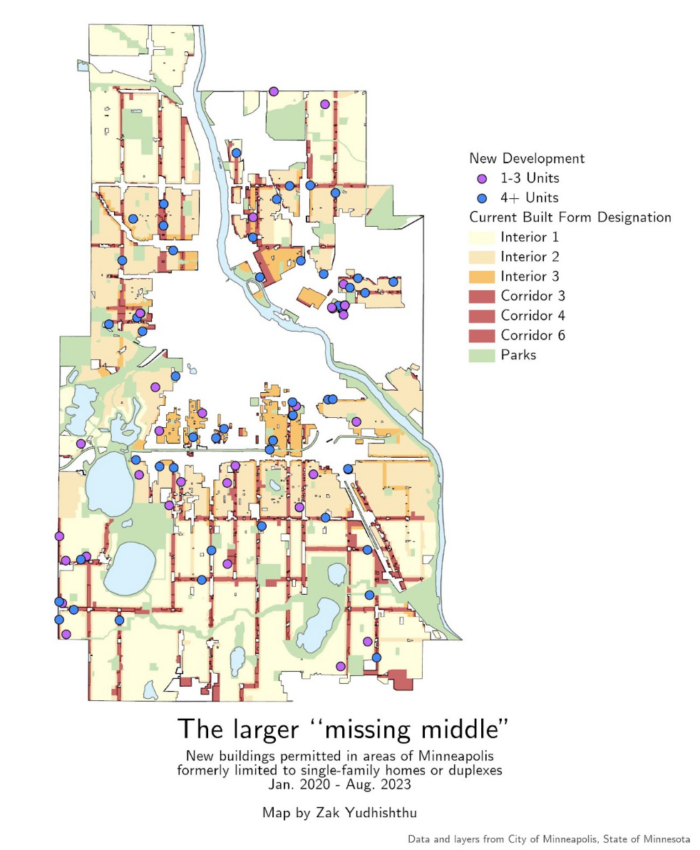

The below map (Fig. 1) shows where Minneapolis builders have added this new housing between January 2020 and August 2023. The shaded-in areas previously allowed only single-family homes or duplexes. In these areas, the dots show new housing that has received building permits from Minneapolis — purple for 1-3 unit buildings, and blue for buildings with 4 or more units. The 4+ unit buildings sum to 1,006 housing units. (Note that not every permitted unit ultimately gets built, but the existence of a permit at least shows that developers initially deemed the project to be feasible.)

Fig. 1

Areas of Minneapolis that previously had restrictive zoning have seen substantial housing development, mostly consisting of projects with four or more units. This new housing has been concentrated along busier arterial streets, which the 2040 Plan designates as “corridors.” Media reports that focus on duplexes and triplexes have mostly overlooked this new housing.

Many of these buildings aren’t huge; they usually have between four and twenty units, and consist of either townhome-style complexes or multiplex-style buildings. The following two figures provide examples of typical projects: Fig. 2 shows ten new townhome units in Northeast Minneapolis, and Fig. 3 shows a six-unit building that is one of the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority’s 16 new small-scale housing developments.

Fig. 2, courtesy of D/O Architects.

Fig. 3, courtesy of DJR Architecture.

Beyond the townhomes and small-scale multiplexes is the next tier of development in Minneapolis: slightly larger apartment buildings, consisting of 20-60 units. Though one of these buildings provides much more housing than a single-family home, they are typically of a moderate scale. See for example the building in Fig. 4, a three-story, 44-unit courtyard apartment building in Minneapolis’s Longfellow Neighborhood.

Fig. 4, courtesy of Corridor.

In these neighborhoods that previously had low-density zoning, a few recent projects in have 60 or more units and a larger scale, such as the below permitted housing development in Northeast Minneapolis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5, courtesy of the City of Minneapolis.

Prior to zoning changes in the Minneapolis 2040 Plan, some of these locations would have only allowed single family homes, and others would have allowed nothing denser than a duplex.

Details Matter

Why is so much of Minneapolis’s new housing in buildings with more than three units? It has to do with specifics in the 2040 Plan rules that govern the built form of new housing.

The lowest density areas in the 2040 Plan, titled “Interior 1” and “Interior 2,” allow for duplexes and triplexes — but with tight restrictions on building heights and floor-area ratio (FAR, or the amount of square footage in a building relative to the lot it sits on). These rules can render make any kind of multi-unit housing infeasible.

The two interior districts each have a 28-foot height limit and a FAR limit of 0.5, meaning that a house on a standard 5,000 square foot lot can be no bigger than 2,500 square feet. This makes it a lot harder for developers to build duplexes and triplexes in those areas.

These restrictions may have been part of a necessary political compromise: allowing duplexes and triplexes in all neighborhoods, but preventing them from being any larger than nearby single-family homes in certain areas. Fortunately, these low-density interior restrictions don’t cover entire neighborhoods.

The corridor districts, which are mostly on busier through streets, have much more flexible rules. Currently, these corridor areas share a low-density feel with neighboring interior areas, as they were not historically zoned for higher density. However, developers can build multifamily projects in these areas that are taller and have more square footage (FAR limits range from 1.5 up to 3.4), increasing the feasibility of moderate-density infill housing.

The resulting buildings aren’t necessarily huge, but the units add up. That’s how the city got 1,006 permitted units out of them over just two and a half years.

Conclusions

Is this a meaningful amount of new housing? Minneapolis typically permits somewhere between 2,000 and 5,000 units of housing per year. A little over 1,000 units in two and half years is not a revolution in citywide housing development, and the city’s headline permitting numbers have not shown an obvious increase in the years since the 2040 Plan was passed. But the growth in permitting is still significant.

It may also reflect an improvement in the distribution of housing development. Even if aggregate housing permits are roughly constant, having some of this housing on newly-legalized sites means more options for residents. This new housing is concentrated along major streets with relatively strong access to public transportation and urban amenities. Much of it is also in high-opportunity areas that previously kept out low- and middle-income households through exclusionary zoning.

Minneapolis’s experience also teaches us some important lessons about effective zoning policy.

Indeed, the 2040 Plan created something of a natural experiment in the effectiveness of different upzoning approaches. Side by side in Minneapolis, we get to compare the effects of a very modest upzoning with those of stronger changes. The modest changes have resulted in few duplexes and triplexes; but where the city took a slightly bolder approach to loosening its zoning laws, developers have sought permits to build in significant numbers.

Other jurisdictions should take note: The details of any given upzoning are immensely important. If cities wish to see new housing in their neighborhoods, they need to get those details right.