Thank you, Los Angeles

Missouri is contemplating stadiums on both sides of the state. Kansas City, facing the transfer of the Royals to new ownership, may consider subsidizing a new downtown stadium to replace Kauffman Stadium, which was renovated in 2011 with taxpayer support. In St. Louis, city leaders are eager to use taxpayer funds to construct a stadium for the new soccer franchise awarded there.

All the economic research literature indicates that stadiums fail to deliver on the promises boosters make about economic development, jobs, and investment. More often than not, wealthy owners and developers simply dangle these new projects before elected officials and voters who are eager to see some sort of new investments in what might otherwise be moribund downtowns. Oftentimes, the threat of losing a team to another market is employed as a type of municipal blackmail.

The owners make more carefully considered decisions when the money being spent is their own.

That is exactly what happened in St. Louis when Rams owner Stan Kroenke indicated he wanted to move the team to Los Angeles. City and state leaders fell over themselves to offer one sweetheart incentive over another. The Rams already paid a ridiculously low rent at the Edward Jones Dome and yet received naming rights, all the revenue from concessions, and almost all of the signage revenue. (Incidentally, St. Louis will continue paying the bonds used to build the Dome until 2021.) To keep the Rams, St. Louis submitted a proposal for building a $900 million downtown stadium with half the cost borne by the public. It was an embarrassment.

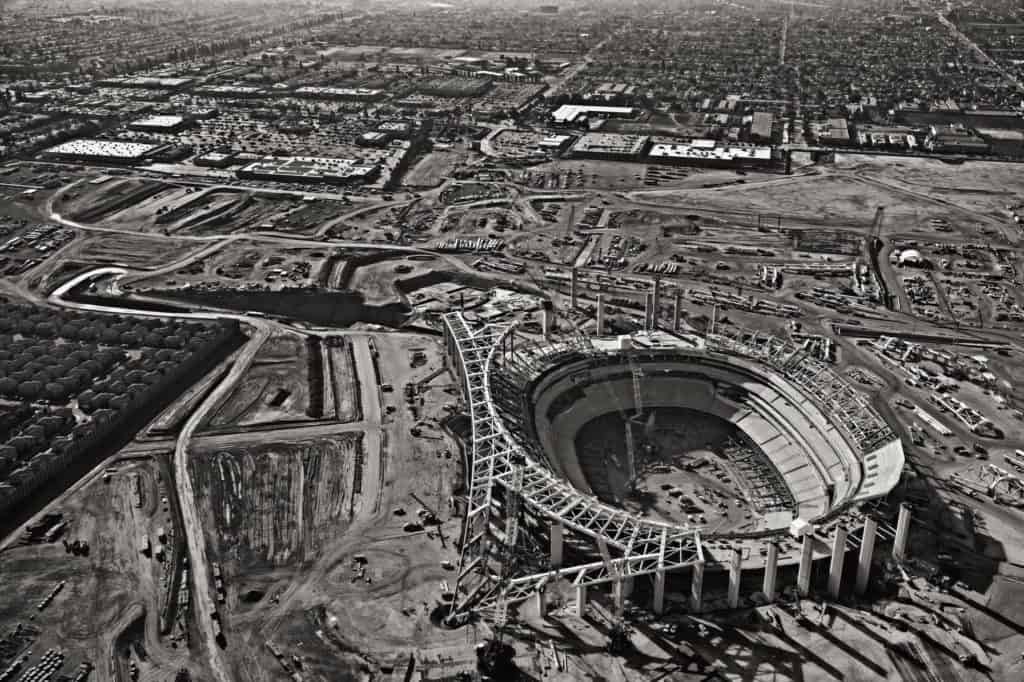

But Kroenke just wanted to move. And he did. As if to prove correct all the economic literature, he did so without any development incentives offered by Los Angeles. In fact, Kroenke put up over a billion dollars of his own money to help construct Los Angeles Stadium at Hollywood Park. And because the investment is his own and others, they are eager to make sure that the resulting park is successful beyond the few games that will be played there each year. In short, the owners make more carefully considered decisions when the money being spent is their own.

This is not the case when public officials spend public funds, and again the St. Louis Rams are a good example. Over the years, city leaders made all sorts of deals with the Rams over and above those mentioned above. In 2024, for example, the Rams will be able to buy a $12 million, 27-acre property that included their indoor practice facility for one dollar.

The fact that the Rams moved to Los Angeles without any sort of incentive is proof that what owners want is a good market in which to operate. No amount of deal offered by St. Louis could overcome that. If cities want to complete with each other, they need to focus on that rather than cutting special deals.

Los Angeles was right to refuse public subsidies to the Rams. Not only will taxpayers be better off as a result, but so will the Rams ownership. The stadium will be built with market realities in mind, not despite them due to easy money from a silent partner with no stake in the game. This is exactly as it should be, and perhaps someday taxpayers across the country will have Los Angeles to thank for leading the way.