For generations, most American cities have required new businesses and homes to provide off-street parking according to arbitrary formulas. To take a typical example, a veterinary clinic in Orem, Utah, must provide one parking space per 325 square feet of floor area. But the same clinic would need just one space per 500 square feet in neighboring Provo.

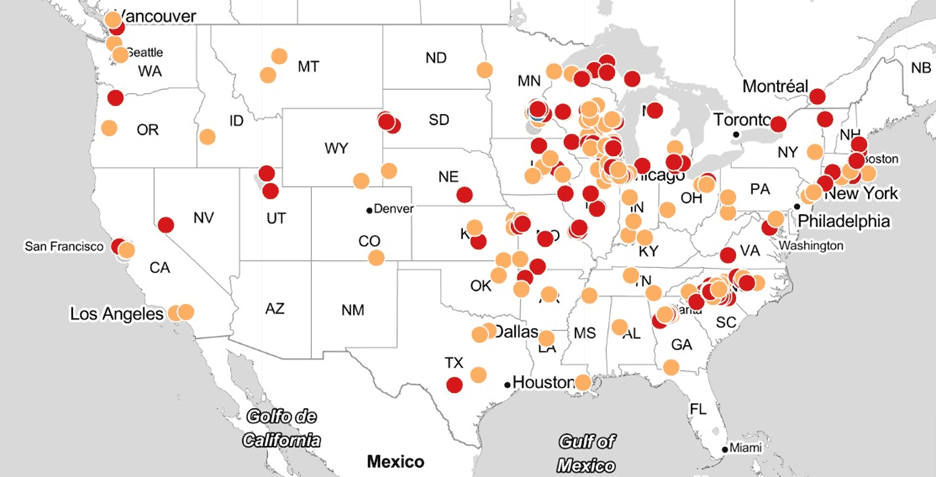

Since 2020, however, scores of cities have ditched arbitrary parking minimums, at least for core commercial areas, letting people balance parking against other priorities without government mandates. But, like fad dieters dropping a zero-fat regime for a daily pound of bacon, some cities have adopted an opposite but equally arbitrary approach. In Nashville (TN), Dunwoody (GA), and Roanoke (VA) parking minimums were replaced overnight by parking maximums. Many more cities, especially in the Carolinas and Upper Midwest, have implemented parking maximums, although most affect only some zoning districts and land-use categories.

A more balanced urban diet is better than either extreme. Each business or builder knows its customers and context best; where parking-related problems persist, such as illegal parking, traffic congestion, or stormwater runoff from parking lots, cities should address those directly on a neighborhood basis.

Motives

Why did most American cities adopt parking minimums in the 20th century? And why, in the 21st, are parking maximums catching on? Weirdly, they’re both trying to solve the same problem: congestion.

Twentieth-century cities saw curb lanes fill up with parked and double-parked cars and vowed to move the stationary cars off the roads, into purpose-built lots and decks. The strategy partly worked – almost any district built since 1960 or so has parking, usually free, well in excess of its needs.

But it also partly failed. Many cities refused to charge for valuable street parking. By making parking so abundant and hiding its costs in taxes and goods prices, the decongested parking areas contributed to congested roadways. With parking “underpriced”, drivers are willing to “overpay” with their time (and other people’s time) by sitting in traffic.

New parking maximums hope to reduce congestion by shrinking the number of “parkable” destinations. But the policy faces the same challenges as parking minimums. It is discouraging that the same urban planners who have come to recognize the failure of solving congestion through minimums now think they can solve it through maximums.

Disinvestment

If underpricing parking led to excess road congestion, why won’t overpricing parking solve it? The failures of parking minimums offer one clue.

When Buffalo, NY, released its downtown from parking minimums for reuse of existing buildings, reinvestment in its long-suffering downtown soared. Smaller developers in particular found relief from parking mandates helpful, since they often work within the envelope of existing buildings. Large-scale developers are still adding and rehabilitating parking structures where there’s demand.

The places where parking problems were worst in 1950 or 1960 were pre-war downtowns, not newly built areas. But the mandates didn’t add parking in downtowns, it just added bureaucratic hassles as each new business occupying an old building needed a waiver from the parking mandates. And the excess congestion cost them just the same: their driving or bus-borne customers, employees, and suppliers were delayed by the general increase in congestion. They doubly lost out.

Fast-forward to today: The places with the most excessive parking lots are largely along major roads in low-density suburbs. Parking maximums won’t, by themselves, induce lot owners to bulldoze existing investments and retrofit them into walkable “town centers.” Instead, it will add a bureaucratic hurdle to every business turnover: seeking a waiver from the parking maximum.

Magic numbers

Parking maximums, like minimums, are based on arbitrary formulas that make no allowance for the diversity of business models. The Institute for Justice successfully sued Pasadena (TX) for imposing a 28-space parking minimum on an auto mechanic whose business needed just five spaces. Under parking maximums, what will become of a business that – for similarly unique reasons – needs 28 spaces when only five are allowed?

Do parking maximums even matter?

Imagine you want to lease space to open a hair salon with four chairs. You’d ideally like 12 parking spaces.

1. At one vacant site on the market, the maximum is 15 spaces and the site owner will build to suit your needs. It’s expensive, but it will work.

2. Next door, the maximum is also 15. There’s an existing building and parking lot with 30 spaces. The landlord won’t shrink it. You can apply for a “variance”, but that will take a few months and requires a public hearing. A lawyer friend assures you that the city always grants variances to reuse vacant structures, but how can you be sure?

3. In a different district, the parking maximum will only allow for eight spaces. The city’s goal is to make this a walkable retail area someday, so it won’t look favorably on a variance request. Can you survive with eight spaces until foot traffic picks up? Or should you cut one stylist?

Parking needs differ even among businesses or residences in the same category. Should a romantic restaurant where patrons arrive in ones and twos have the same parking as a kid-friendly pizza place that mostly attracts minivans? Do we expect a retail store selling appliances to have similar traffic patterns to one selling bikes?

If cities enforced parking maximums strictly, businesses needing more parking than allowed would decamp for neighboring jurisdictions. What seems more common is a continuation of the delays and uncertainty of the waiver process: the same arbitrary numbers and kludgy governance that prevail with parking minimums.

Everybody pays

Suppose a city embarked on a successful, multi-pronged effort to reduce its total parking – eliminating not just excess parking but in-demand parking as well. On the plus side of the ledger, they would have freed up space for other valuable uses, like homes, jobs, recreation, and commerce. But the city might find itself with the double parking, cruising, and curbside congestion that originally made parking minimums seem like a good idea.

It’s an unpopular economic truth: Everybody pays. People pay with their time – by sitting in traffic or cruising for parking – if they can’t pay with their wallets. Tolls and parking meters reliably keep traffic flowing and parking available where mandates and prohibitions both fail.

Better alternatives

If parking maximums are a bad idea, how can city leaders meet the goals that led them to revise parking policy in the first place?

- Reduce congestion on the roads.

- Price all public parking at the market rate. This cuts down on cruising for parking.

- Regularly re-optimize traffic lights. This cheap, effective way to get the most from existing roads (and improve safety) is surprisingly underrated.

- Implement highway tolls and downtown decongestion fees, which are the only proven remedy for widespread congestion.

- Implement traffic circulation plans to keep through traffic moving along the outskirts of small commercial districts while local-destination traffic comes in and out.

- Reduce stormwater or heat island effects in new developments.

- Require newly constructed parking areas to capture and offset runoff.

- Require landscaping and tree cover at parking lot edges. As a bonus, this makes parking easier on the eyes.

- Mitigate runoff or heat island effects for old parking lots, funding it either through general revenues or by special assessments on those that are creating the problem.

- Replace driving trips with walking or transit.

- Upzone to allow more residents, jobs, and destinations in walkable, transit-rich locations, thus using existing infrastructure more efficiently.

- Prioritize walkable locations for government buildings, especially schools.

- Address barriers to walking, such as unsafe crossings.

And don’t forget to eliminate parking minimums. They’re just as bad as parking maximums.