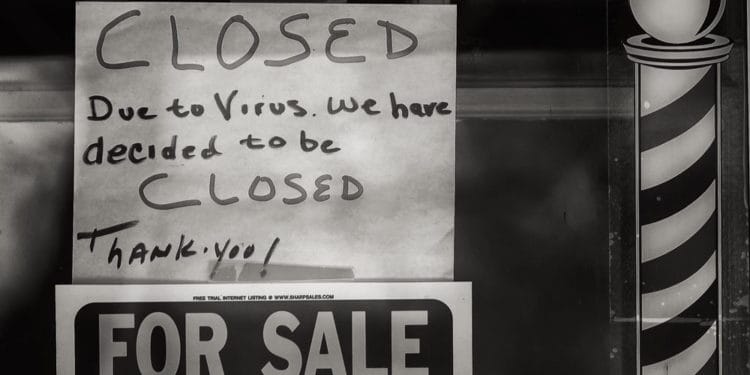

COVID-19 shutdowns are posing a new set of challenges for state and local governments because the longer they impact people and their businesses, the greater the chances that they will be sued for damages. When a governmental agency severely restricts the use and value of private property, whether by onerous regulations or permit denials, the agency is potentially liable for a variety of constitutional challenges — regulatory takings, due process, and Contracts Clause challenges.

With more people chaffing under shutdown rules, some of which may last for many months more, some are turning to the argument that the destruction of use and value by the orders is a taking. If that is true, then the property owners could be entitled to damages under the state and federal constitutions that prohibit the taking of property without the payment of just compensation.

Filing such a claim, however, is not the same as winning.

To start, property owners will face a fundamental hurdle: the emergency exception to the Takings Clause. When property is threatened with destruction by fire or enemy troops, governments have destroyed some property to protect public health and safety. Thus, homes have been torn down to create a fire break when a city has become engulfed in a conflagration. And in one famous case, the United States blew up an oil terminal before Japanese troops could take it over during World War II. In these cases, courts invoked the emergency exception to takings liability. Part of the justification was that the property would have been rendered useless and valueless by the fire or enemy troops and the government’s action created no additional harm. Courts must determine whether the shutdowns are the functional equivalent of such emergency orders.

While a business may temporarily lose all use and value during a mandated shutdown, does it make a difference that the shutdown is only temporary? Already, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has ruled that the temporary nature of the action eliminates takings liability. Surely, the last word on that defense has yet to be heard, but property owners bringing shutdown-related takings claims must deal with that argument.

Moreover, the basis for a takings claim is that the government action has destroyed the use and value of property. But can it really be said that the loss of use and value was all due to the government shutdown? How many people would voluntarily go to work or shop in a nonessential store or restaurant knowing there is a pandemic raging and they could die as a result? If these takings lawsuits proceed, there will be much argument over how much economic damage was caused by government orders, compared to the damage caused simply by the pandemic.

But as difficult as these questions are, the longer the shutdowns persist, the weaker government justifications will become. In flooding cases, there is the adage that if water covers an area for a week, it’s a flood, but if water covers the same area for many years, it’s a lake. In the case of COVID-19, when is a public health emergency no longer an emergency but a background factor in how people live their lives? There must be a finite duration to the shutdown orders if people are not to starve — even if that means a heightened risk of disease. But if government shutdown edicts persist beyond the emergency phase, it will be harder to justify any emergency immunity from liability.

There are other avenues besides takings lawsuits to alleviate the costs of the shutdowns on property owners or businesses.

There are other avenues besides takings lawsuits to alleviate the costs of the shutdowns on property owners or businesses. As we continue to learn from experience, the shutdowns must be imbued with flexibility and a process for relief. In other words, if a business thinks it can prove that it can successfully implement protocols to protect employees and the public from disease, it must be given an opportunity to try. The Due Process Clause of the Constitution requires this. Based on existing precedent, courts can weigh the harm to the property owner, the necessity for the government action, and the practicality of fashioning some meaningful relief. But governments must provide a mechanism for seeking such relief. Otherwise, they can be sued for a violation of due process.

Finally, there is some push in some states to create rent holidays, wherein tenants affected by COVID-19 cannot be evicted for a failure to pay rent. Some proposals go even further and seek to declare that back rents can never be collected, or collected only in a year or so — penalty- and interest-free. These proposals go beyond anything that was tried in the past, even during the Great Depression. More importantly, they stand in direct violation to the Contracts Clause in the Constitution which declares that no state shall pass any “Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.” Passed in response to attempts in some states to wipe out debts owed by farmers during a post-Revolutionary War recession, this clause puts severe limits on the ability of governments to eliminate the obligation to pay rent.

The COVID-19 shutdowns have already spawned litigation. More will come. While these suits will initially be difficult to win, the longer the shutdowns last, the more likely it is that property owners will find some measure of relief. We must never forget that emergencies, no matter how grave, do not create holes in the Constitution.

Beyond the spectacle, Kansas City prepares for World Cup reality