The recent Memorial Day weekend produced news reports and social media videos of packed beaches and crowded urban parks as people, months into government-imposed shelter-in-place orders aimed at fighting the coronavirus pandemic, looked to enjoy the ceremonial start of summer.

With decreased vehicle traffic during the coronavirus shutdowns, many major cities are closing streets to create more outdoor spaces for both public and private uses. San Francisco, Oakland, Minneapolis, New York and Seattle are among the many cities creating public spaces out of roadways.

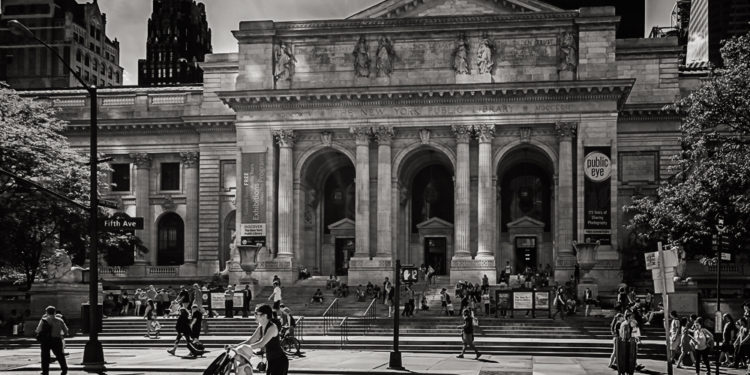

This “open streets” movement seeks to transform roadways into the pedestrian- and bike-exclusive corridors, limit through-traffic, and decrease speed limits—with the goal of creating outdoor spaces conducive to social distancing. New York’s 40 miles of open streets operate daily from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., in line with police staffing availability, and the city looks to expand the program to a total of 100 miles.

Oakland says its “slow streets” will ultimately stretch for 74 miles. Even smaller cities, such as the Boston suburb of Brookline are increasing sidewalk widths and creating temporary bike lanes.

Hoboken, New Jersey, has repurposed street space for private purposes, allowing local restaurants to create outdoor seating in a previously public rights-of-ways. These “str-eateries” allow patrons to eat at restaurants with a decreased risk of contamination, providing a lifeline for local establishments. In Cincinnati, eight restaurants have opened seating in closed roadways or former parking lanes in the historic Over-the-Rhine neighborhood.

Open streets have the immediate public health benefit of decreasing crowding when outdoor space is in high demand, but some activists want to make these changes permanent.

Outlier events should not be the basis for permanent changes to a city’s infrastructure. An open street is more of a novelty than a sustainable practice, similar to a carnival set up in a municipal parking lot or a sidewalk sale on Main Street.

Permanent open streets are analogous to previous “road diets” attempted in cities such as Los Angeles, where road capacity was artificially decreased to slow traffic and discourage driving.

Take for example New York City’s open streets pilot program in March, which was suspended within 11 days. The city found there was not enough usage of these spaces to justify the necessary policing cost. In May, New York City tried again, as the warming weather increased demand for outdoor space.

In the short-term, cities could restrict the pedestrianization of streets to holidays and weekends during the summer. And any city looking to create open streets should first open its parks and outdoor recreational facilities. Additionally, as the stay-at-home orders are lifted and the economy recovers, cities need to ensure they have adequate road capacity to meet the demand of returning workers, students, and customers.

Permanent open streets are analogous to previous “road diets” attempted in cities such as Los Angeles, where road capacity was artificially decreased to slow traffic and discourage driving. Anti-car activists hoped that road diets would make driving so inconvenient in the urban core that individuals would choose to take mass transit or active transport options, like walking and cycling.

While adult leisure bike sales are up 121 percent during the coronavirus pandemic, as people seek ways to get out and exercise, active transport is not a realistic mode of commuting for most suburban and exurban workers.

Open streets do temporarily address weather-dependent increases in demand for outdoor spaces and open up the opportunity for outdoor seating to help restaurants. In the long-run, however, adequate parking and vehicle access are required to attract customers and employees. Decreased road capacity also hinders the freight industry, increasing delivery times and costs, particularly in urban cores.

In the second half of the 20th century, pedestrian malls were a go-to method for cities trying to revive their downtowns in the age of the shopping mall. But few remain today. Cities temporarily allowing the use of open streets this summer during the pandemic is one thing but cities thinking they can keep cars off of major streets permanently will likely repeat the costly economic failures of pedestrian malls.

What Missouri can learn from Kansas’s budget crisis