Focused Advocacy’s three partners have years of experience under the pink granite dome of the Texas Capitol. Founder and CEO Curt Seidlits, 66, served for a decade in the legislature. Brandon Aghamalian, 46, was Fort Worth’s director of government relations. And Snapper Carr, 45, was legislative counsel for the Texas Municipal League.

All three are breathing a bit easier these days after escaping what could have been a catastrophic blow in the recently ended session. For weeks, local officials and lobbyists watched anxiously as a bill that would have severely restricted lobbying by cities, counties and other local government entities advanced through the legislature. The bill died in the Texas House just days before the session ended.

The measure would not have affected salaried in-house government affairs employees who advocate for cities and counties. But it would have barred cities and counties from spending money on outside lobbyists such as Focused Advocacy. Those firms earn millions of dollars arguing for local officials before state lawmakers during each biennial session.

The measure is likely to return when the legislature reconvenes in 2021 — a stark illustration of the widening chasm between conservative state lawmakers and liberal city officials in Texas and many other states.

At the state level, Republicans dominate Texas. The GOP has controlled both legislative chambers since 2003, and it has held the governor’s mansion — and every other statewide office — since 1995.

But Texas cities, where an increasingly large percentage of Texans live, tell a different story. Houston, San Antonio, Dallas and Austin lean Democratic. On issues ranging from immigration to plastic bag bans to protecting old-growth trees, cities have defied the state’s conservative leadership, only to have state leaders rein them in. The proposed lobbying ban significantly escalates that fight.

“You know, at one point I thought it was mostly directed at Austin,” said the city’s Democratic mayor, Steve Adler, describing the traditional friction that defines the relationship between his city and Texas lawmakers. “But in the last session or two, it’s become apparent that it seems to be directed to cities more generally.”

The anti-lobbying bill would have had a withering impact on the hundreds of outside lobbyists that represent cities, counties, special districts and other local government entities in Austin. It also would have prohibited the payment of dues by cities and counties to lobbying organizations such as the Texas Municipal League and the Texas Association of Counties.

In addition to lobbying, the Municipal League runs workshops, provides legal support to cities and helps them develop long-term plans. But the bill would have eliminated one of its most important functions: advocating for cities before the legislature.

“We would have gotten out of the advocacy business,” said Bennett Sandlin, the group’s executive director. “It would change our organization pretty dramatically.”

City and county governments vehemently protested the ban, saying it would silence the voices of their residents.

State Rep. Travis Clardy, a Republican from Nacogdoches who opposed the bill, said local officials in his largely rural district seek professional representation in Austin for the same reason they hire a plumber or a landscaper. “It means you hire people who are skilled at government relations that know what doors to knock on and where to go,” he said.

But supporters of the measure — among them the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation — said publicly funded lobbyists often advocate policies that aren’t supported by many of the residents of the cities and counties they represent.

“It is fair to say that ending taxpayer-funded lobbying is the foundation’s top goal moving into next session,” said James Quintero, director of the Austin-based think tank’s center for local governance.

A 2017 report by the foundation found that governmental entities spent as much as $41 million on outside lobbyists during that year’s legislative session, based on a review of lobby expenditure reports filed with the Texas Ethics Commission. The amount constituted 11% of the total $376.6 million in lobbying expenditures in 2017, the report said.

The figures are the latest available, but Quintero said foundation researchers are working to determine the amount spent in 2019.

“It’s just not right that our local property tax money is diverted to the pockets of Austin lobbyists,” said state Rep. Mayes Middleton, a Republican who represents Wallisville, about 40 miles east of Houston. Middleton sponsored the House version of the ban. “And that’s money that can’t be spent on potholes or teachers and police and fire.”

State Rep. Matt Krause, a Fort Worth Republican, said the state is trying to “rebalance” the city-state dynamic in response to what he called “unconstitutional” actions by cities, such as requiring employers to offer paid leave and outlawing the oil and natural gas extraction technique of fracking.

“We’re seeing that over and over here in Texas, where local governments try to do something they don’t have the authority to do,” Krause said.

Although GOP state leaders lost on the ban, they prevailed in several other fights with cities during the session. They curtailed local property taxes, reduced cable franchise fees paid to cities and relaxed regulations of building materials for new construction. The Texas Municipal League, warning that cities were “under siege,” rallied city leaders against those measures but were unable to stop them.

“It was a rough session,” Sandlin said.

An uneven playing field?

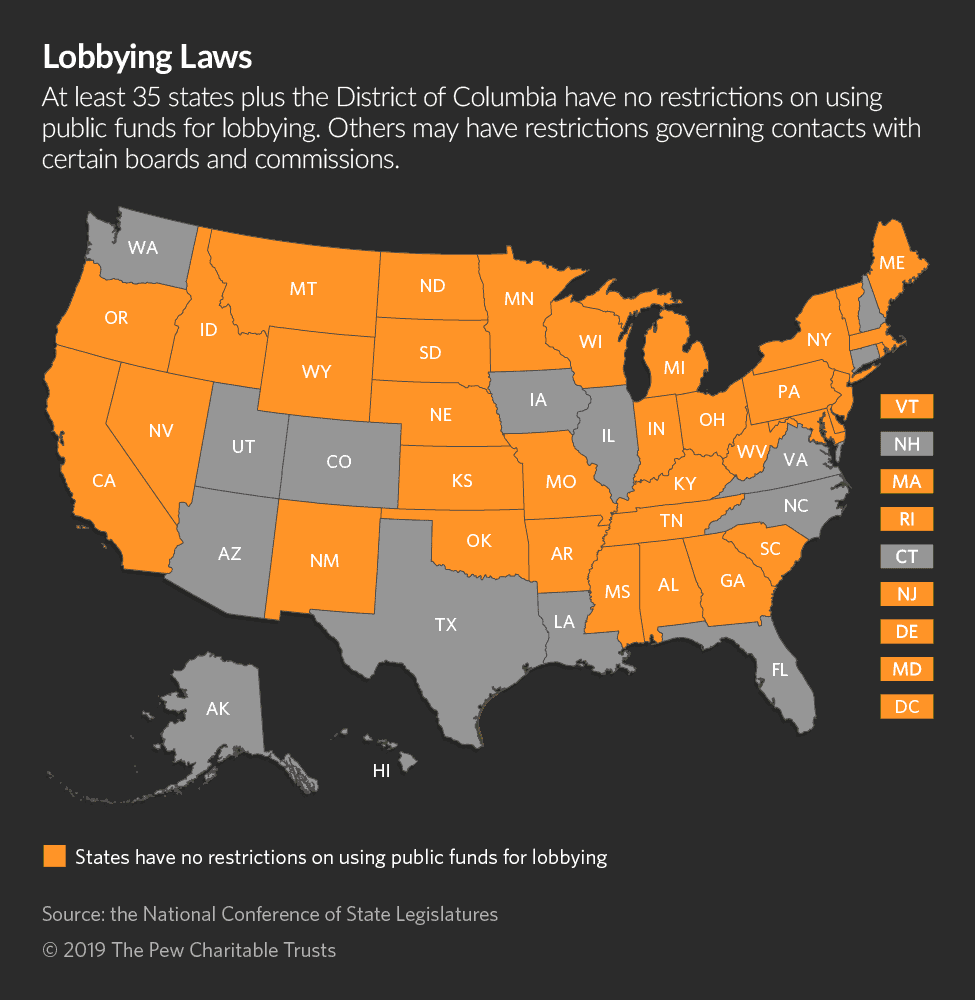

At least 35 states plus the District of Columbia have no restrictions on using public money for lobbying, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. The report lists Texas as one of those having restrictions because it prohibits state agencies from lobbying lawmakers.

The effort in Texas is the first serious state legislative attack on cities’ ability to lobby, said Brooks Rainwater, who heads the Center for City Solutions at the National League of Cities.

“There have been limited efforts around the country that have not gotten traction,” Rainwater said, “because residents understand the value of having their local elected officials’ voices heard in statehouses.”

Bill Kelly, director of the four-member government relations team in the Houston mayor’s office, put it a different way: “If you’re not at the table, you’re going to be on the menu.”

The Houston City Council allocated up to $662,000 over two years for outside lobbyists to advocate for Houston in the statehouse, and another $744,000 for lobbying in Washington, D.C. One 2019 success: obtaining $200 million from the state for Hurricane Harvey recovery efforts.

Austin allocated $596,250 for outside lobbyists in 2018-2019: $165,000 for the Focused Advocacy team and $431,250 for six other lobbyists. Fort Worth spent $224,000 on state advocacy efforts, including $73,000 to McGuireWoods LLP.

“I’ll call it advocacy, not lobbying,” said Fort Worth City Manager David Cooke. “Cities and towns have different needs. Each of these towns and cities knows best what their community wants.”

But Jon Russell, the national director of the American City County Exchange, an affiliate of the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), said city and county officials in his organization would welcome a ban on publicly funded lobbying.

“It’s one of the top issues for our members,” said Russell, a town councilman in Culpepper, Virginia. He said municipal leagues and associations often stake out positions that are “not reflective of many of my members.”

Source of a scandal

Even though the anti-lobbying bill flamed out this session, its repercussions are still rippling through Texas politics.

Just weeks after Texas Monthly magazine named Republican House Speaker Dennis Bonnen one of the state’s eight best legislators, he was accused of privately trying to persuade a conservative activist to campaign against 10 moderate House Republicans (including Clardy of Nacogdoches) in the next election.

All 10 lawmakers broke ranks to vote against the lobbying ban.

The activist, Michael Quinn Sullivan, the president of Empower Texans, ignited the scandal by alleging that Bonnen and Republican state Rep. Dustin Burrows of Lubbock offered House media credentials to Sullivan’s organization in exchange for campaigning against the lawmakers. Sullivan taped the meeting.

The case, which has raised the specter of bribery, is now under investigation by the Texas Rangers and the outcome is far from certain. Bonnen has apologized to House members for the meeting with Sullivan and for saying “terrible things that are embarrassing to the members, to the House, and to me personally.”