While digging through the rich history of Santa Barbara, California, I stumbled upon a story from the early 1980s that forever changed how I see my hometown. Back then, as Reaganomics was making waves and young people were glued to MTV, a group of “progressive, environmentally minded” planners came together to craft a study called “The Impacts of Growth.”

The gist of this “study,” as far as I can tell, was to scare Santa Barbarans into limiting housing production by insisting that growth would degrade their quality of life and be bad for the environment. As Rich Appelbaum, one of the study’s authors, explained in a 2015 interview:

The standard approach was to project out past trends, thereby creating a self-fulfilling prophecy requiring public officials to accommodate to the prediction … [we] would have none of this. The study … had many impacts of its own. It led to a down-zoning, both commercial (the driver of growth) in the form of a city charter amendment … and residential. The study and city’s approaches were considered to be models — what today would be called “best practices.”

In a groundbreaking move, the city voted to cap its population at 85,000 — a decision that would shape the next 30 years. Practically speaking, this meant that the Planning Commission made sure to never approve more units than could house that many people.

When asked whether the study had achieved its goals, Appelbaum admitted, “It is clear that many of the people who work in Santa Barbara are priced out of the local housing market … I would say that growth control in Santa Barbara has had mixed results … [it’s] contributed, in part, to higher housing costs.” Oops.

Fast forward to today, and Santa Barbara’s population has crept up to around 91,000. I moved here in 2010, making me one of the “illegal” 6,000 residents. However, despite the population cap, locals still view housing as a closed system. Many argue that if the city grows any further, traffic will worsen, pollution will spike and we’ll run out of water. And thanks to “The Impacts of Growth” curbing housing production for decades, some even believe that we’ve narrowly dodged disaster. But is that really the case?

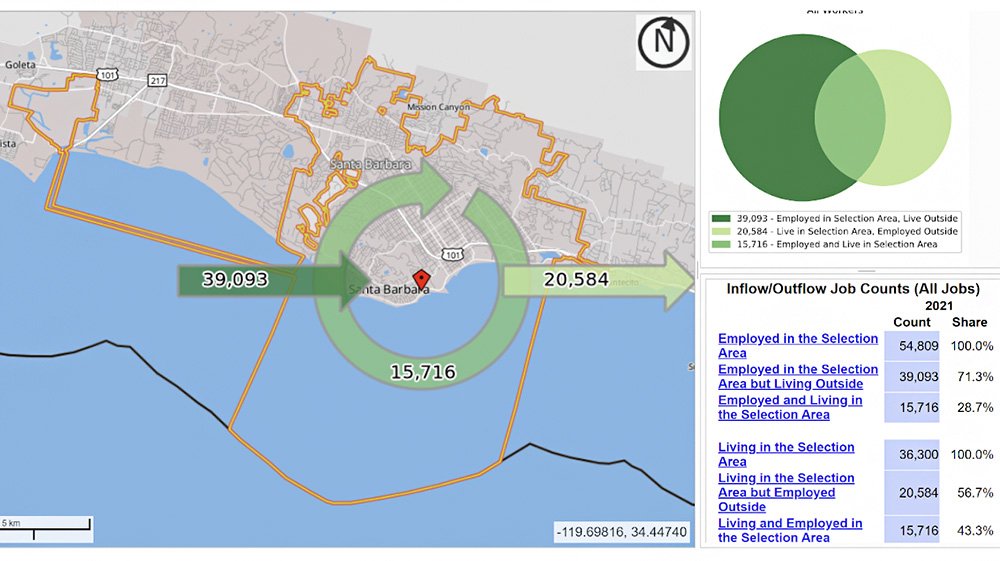

Statistics tell us a very different story. Around 40,000 people commute into the city of Santa Barbara each day as of 2021. That’s 71.3% of people who work in the city. Further analysis shows that around a third of these people live over 50 miles away. Meanwhile, the populations of Santa Maria, Lompoc, Ventura and Oxnard — towns that didn’t have anti-growth policies — have increased by the tens of thousands, collectively. This happened because, although we limited housing production, jobs continued to grow. At the same time, when a teacher or nurse in Santa Barbara retires and sells their home, it is often bought by someone in a higher socioeconomic strata. This means that the new teacher or nurse has to live somewhere else.

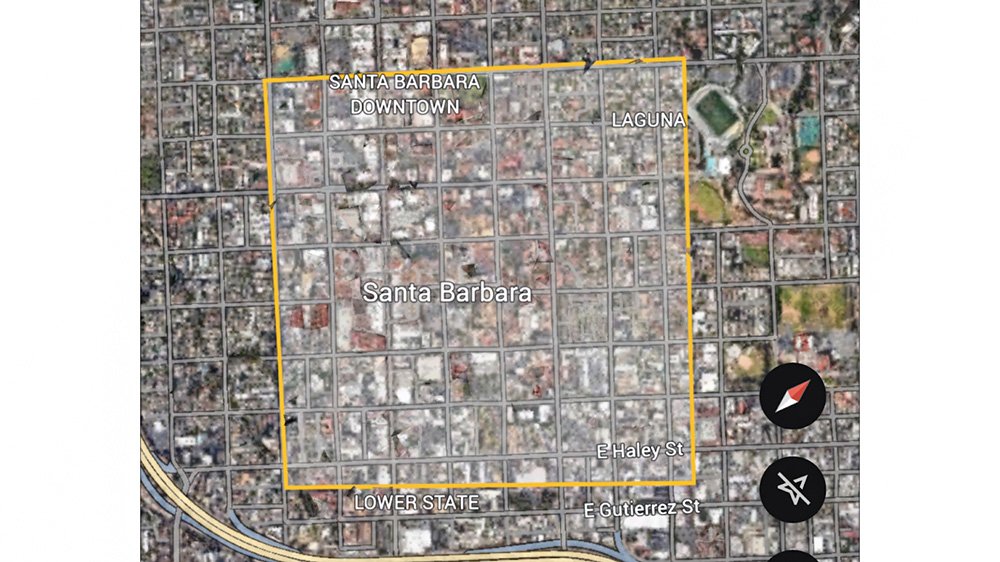

Many of these commuters could have been housed in apartments, duplexes, or backyard cottages built over the last 30 years around our city. We also could have strategically densified our downtown, keeping most new construction and residents on a small fraction of our city land. As I’ve written before, new residents living downtown would be far more likely to walk, bike or take transit to work as they’d be far closer to jobs. Strong Towns Santa Barbara (the city’s Local Conversation) member Alex Gravenor recently calculated that it would take about 350 acres of five-story buildings to house a majority of these commuters. Make the buildings six stories and the land area shrinks further.

Of course, this housing wouldn’t actually appear as a monolithic square but would be spread throughout our downtown — and it turns out there’s plenty of room. Last year, we partnered with the Parking Reform Network to create a map and found that 27% of our downtown (the area zoned for the highest density) is off-street parking. Turn those lots into housing (perhaps putting the parking underground), and you’ve nearly solved the problem.

At the end of the day, instead of slowly densifying areas of our city core or replacing ugly asphalt lots with pleasant Spanish-style buildings, we’ve created a population of people who spend hours of their day commuting to our city. This has caused far more traffic and pollution stretched over a farther distance than if we had allowed our city to grow. These commuters use just as much water from the local watershed as if they lived next door. And most sadly, all the time these people spend commuting is time they could be with their friends and families.

Commuting actually has all sorts of adverse effects: The longer your commute, the more likely you are to get divorced. Your blood sugar and cholesterol levels will be higher. You’ll be 21% more likely to be obese. It will be harder for you to fall asleep at night. You will spend less time with your friends and feel more lonely. Meanwhile, the environmental costs of all these extra cars on the highway go without saying. Not to mention the increased infrastructure costs to maintain roads with heavy usage or justification for multimillion-dollar widening projects like the one in Montecito, which is unlikely to affect travel times.

Strong Towns Santa Barbara proposes that we need to welcome growth. We can’t keep pushing the growth that should be occurring here to cities 20+ miles away. Yes, we can be thoughtful about where new buildings go and how they look, but we can’t refuse to change. Residents of buildings in the city will be far more likely to walk or bike to work. Even if they drive, their 1-2 mile commutes will cause less traffic than if they come from 50 miles away. And no, demand isn’t infinite, and the relationship between supply and demand is real. As British Columbia Housing Commissioner Uytae Lee puts it:

Preventing new housing from being built doesn’t get rid of the demand for new housing, it just shifts that pressure onto older housing. In a housing market where we continue to build new housing supply, the people who are willing and able to pay more for their housing tend to move into newer and more expensive housing. And over time, those newer and more expensive homes today often become the older and more affordable homes of tomorrow — as long as we continue to build new housing. But when we don’t build new housing, we just put pressure on the overall housing market.

The few cities that have built new housing have, in fact, seen a stabilization in rent prices, even in coastal California. If we want to replicate that in Santa Barbara, we can start by building units for those who already commute here and see where we can go from there.

Though well-intentioned, the planners behind “The Impacts of Growth” created an upward spiral of unaffordable housing that has made owning a home in Santa Barbara an unattainable dream for most. However, we can begin to reverse this damage. For the sake of the environment, affordability and quality of life, we need to build more and denser housing locally.