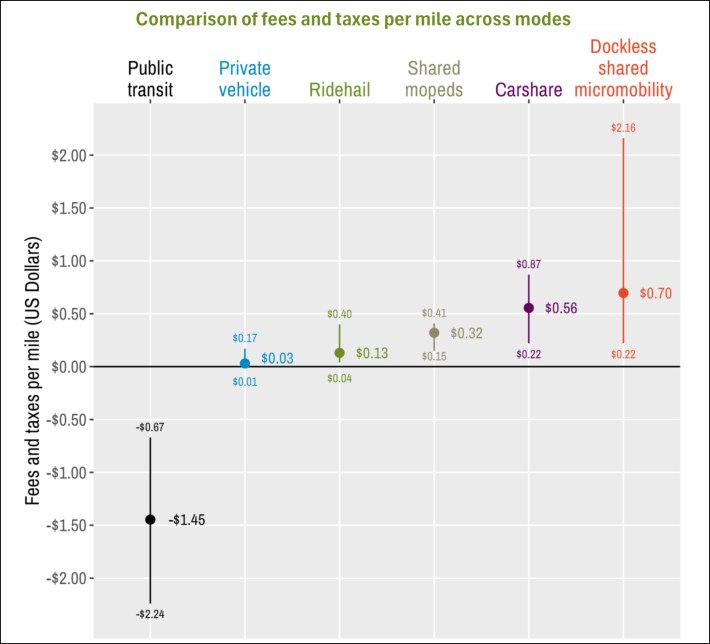

According to the study from researchers at Portland and Sonoma state universities — and, full disclosure, Lime, the scooter company — the average trip on a shared micromobility mode, such as a scooter, includes about $.70 per mile in fees and taxes levied by municipalities.

Meanwhile, the average motorist pays about $.03 per mile in such fees.

“There is certainly a frustrating inconsistency in how cities talk about prioritizing sustainable transportation options and actions they take in applying fees and taxes to driving versus micromobility,” said Calvin Thigpen of Lime. “Unfortunately, policymakers at every level often defer the hard questions about increasing the cost of driving.

“Nowhere is this clearer than in New York, with the 11th-hour collapse of congestion pricing,” he added. “It’s deeply disappointing that we’ve apparently lost a once-in-a-generation opportunity to set a new precedent in North America to begin to appropriately price the negative externalities of driving.”

The report found that governments across North America take on average nearly 14 percent of fare revenues in the form of sales taxes from riders, who are in a sense double-taxed because cities often also charge an operating fee to shared micromobility companies, a fee that is typically passed onto the consumer.

Fourteen of the 15 cities that take in the most per mile in annual fees as a percentage of fare revenue are in North America.

The problem with that? “Fees directly impact the financial performance of companies and thus the viability of their shared micromobility programs,” the report says. “All else being equal, lower fees increase the probability that shared micromobility companies can sustain operations over time.”

Meanwhile, car drivers and taxi passengers are getting a (nearly) free ride. Shared micromobility fee and tax rates are “high relative to most other modes of travel, notably personal vehicle travel (23 times more per mile) and ride-hail trips (over five times more per mile),” the report said.

And the federal gas tax has remained flat for several decades, losing ground against the rising costs of maintaining and building road infrastructure.

The authors of the study, John MacArthur of Portland State University, Kevin Fang of Sonoma State University and Thigpen, admit that they don’t know the “optimal fee amounts” that cities should charge, but argue that cities must figure out the best way to avoid overcharging.

“We recommend that cities align fees with overarching municipal transportation [sustainability] goals and use well-established principles of taxation and administration to determine the structure of fees,” the pair wrote.

In an interview, Thigpin said that this is the moment for cities to act.

“The survey results suggest cities are aware that high fees contribute to lower ridership, but most don’t see this as a priority when weighed against concerns like covering administrative costs, or even adding a new revenue stream,” he said. “We’d love for cities to think about this as a policy decision — because that’s ultimately what it is — and instead consider the impact of fees and other costs in the context of achieving their transportation equity and sustainability goals.

“So as cities revisit their program regulations, we hope they recognize the industry has matured substantially since fees were initially established — with safer vehicles, better operations, and closer city collaboration,” he added.